What’s All This Fuss About Wildlife Habitat?

By Chuck Blair, Golden Eagle Guest Blogger

My Golden Eagle blogs will focus on wildlife habitat and the importance of preserving and enhancing it at every opportunity. The title is based on fond memories of Gilda Radner’s SNL character, Emily Litella, making exhaustive and impassioned pleas during the Weekend Update news segment in the late 70s. The topic of one of these skits was “What’s all this fuss about endangered feces?” She droned on and on about feces being endangered, how it wasn’t possible, and questioning why people were so concerned about it. After several minutes Chevy Chase politely interrupted and whispered in her ear that the issue was “Endangered Species”, not “Endangered Feces.” To which Emily replied, “Oh, that’s different! Never Mind.”

As fellow Audubon members and birders, you understand that habitat for wildlife is important. I will explain the many fascinating elements that make up “habitat.” You can look forward to a series of blogs focused on what habitat is, what makes it good or not so good, how it changes over time, how size and diversity matter and many other topics. Increased understanding will kindle concern and engagement over local, state, and national habitat issues that affect the places and critters we love.

It All Starts With Plants

Plants evolved to grow and reproduce in places that meet their requirements. Climate is the major factor affecting the types and diversity of plants that grow at a site. Climate determines the average temperature and precipitation, when that precipitation occurs, the length of the growing season, and the quality of the soil, including levels of soil nutrients. Optimal growing conditions, which vary from plant to plant, must include adequate space, food, water, light, temperature, air, aspect, and other factors. The main drivers of plant distribution are:

Space – is there enough suitable area for larger plants to grow?

Food – what nutrients are available in the soil?

Water and humidity – is there adequate water at the appropriate time of year for germination, flowering, seed set, and fruit development?

Light – is there full or partial sunlight or dense shade from taller plants?

Temperature – what are the seasonal temperature extremes and how long is the growing season?

Air and wind - is there adequate oxygen in the soil for plant respiration and the release of carbon dioxide and for respiration and metabolism by soil microorganisms? Higher winds accelerate evaporation so windy areas dry more quickly, which affects the types of plants that can grow.

Aspect – aspect is the direction that a hill or mountain slope faces. It is a key driver of native plant distribution in the mountains of Idaho and the West because it affects most of the elements described above. South facing slopes are drier than north facing slopes because evaporation is higher, and less snow accumulates on south slopes. South facing slopes dry out faster in the spring and early summer, which results in grasses and small shrubs occupying drier south slopes and larger shrubs and trees, which require more moisture, on wetter north slopes.

Elevation and latitude – these are major drivers of plant distribution as they affect many elements of climate.

Temperature, water and humidity, sunlight, wind, and aspect all come together to determine where suitable growing conditions exist for different plant species. Consider the difference in vegetation shown in the Google Earth photos below.

On the left, are low elevation, generally south facing foothills south of Lucky Peak Reservoir. Note the uniformly tan color of dried grasses and a few low shrubs such as sagebrush and rabbit brush.

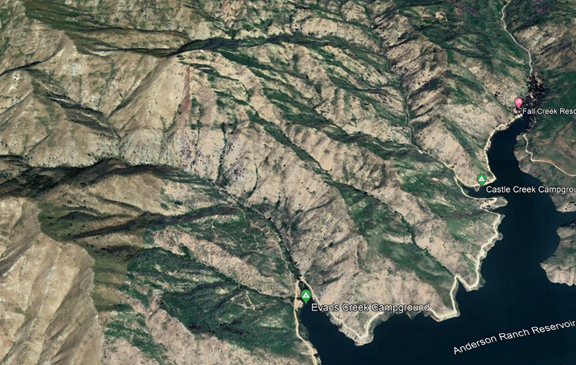

In the center, you see higher elevation foothills north of Anderson Ranch Reservoir and the effect of aspect on plant distribution. Note the contrast between dry (tan colored) south facing slopes supporting mostly grasses, forbs, and dryland shrubs. and wetter (green) north and northeast facing slopes supporting a variety of deciduous shrubs and conifers.

On the right is the Boise River in the vicinity of Willow Lane. Aspect is not an issue here because the area is flat. However, much higher yearlong soil moisture levels exist here than at the other sites because of the proximity to the Boise River. These conditions support robust growth of riparian species including black cottonwood, river birch, several species of willow, and many others.

What does it all mean for wildlife?

How does the type and distribution of vegetation translate into habitat for different types of wildlife?

Habitat is the physical and biological setting in which organisms live and in which the other components of the environment are encountered. The concept of habitat is critical to modern ecology and was adopted and promulgated in some of the earliest treatises and texts. It is a basic requirement of all living organisms. Habitat is one of the four components of a species' environment, along with climate variables, nutrients, and other interacting organisms.

Wild animals require four basic habitat components--food, water, cover or shelter, and space. The place where an animal gets all these things is called its habitat. Some living things can only survive in very specific habitats – where the air is a certain temperature, the soil a particular type, or a certain food can be found. The amount and distribution of these habitat components will influence the types of wildlife that can survive in an area. The specifics of these requirements vary greatly from one species to another, as well as from one season to the next.

Food sources might include insects, plants, seeds, fruit, or other animals and often change with the seasons. Many animals must make seasonal migrations to find enough suitable food. These movements may cover several thousand feet up and down a mountain or many thousands of miles across continents and oceans.

Burrowing Owl in sagebrush-steppe habitat by Ken Miracle

Water sources may be as small as drops of dew found on grass or as large as a lake or river. Some animals get most or all the water they need through succulent foods like fruits. Other animals, such as wetland-dependent species, will not be present unless there is a nearby stream or marsh available. Generally, the larger and more diverse an area is, the more species of wildlife it can support.

Common Loon with crayfish by Louisa Evers

Wildlife need cover for many life functions, including nesting, escaping from predators, seeking shelter from the elements on a cold winter day, and resting. An underground burrow, a cavity in a tree, or even plants along a road might provide cover for a den or nest site. A brush pile provides escape cover for rabbits and other small mammals, while evergreens provide nest sites for birds in spring and thermal cover for wildlife in winter. The amount and types of cover available will, in part, determine the species of wildlife found in a given patch of habitat.

Animals also need space in which to perform necessary activities such as feeding or finding mates. The space an animal needs and over which it travels is referred to as its home range, which is the area in which the animal normally lives. As a general rule, large animals have larger home ranges than small animals, and large areas of undeveloped habitat are better for most wildlife.

For example, home ranges of individual wolverines are generally extremely large, but vary greatly depending on availability of food, gender, age, and differences in habitat. Home ranges of adult wolverines range from less than 40 square miles (mi2) to nearly 350 mi2. On the opposite end, meadow voles, shrews, and other small mammals may live out their entire lives within a single acre or less.

Next time we’ll dive into the concepts of home range, territory, habitat patch size, and related topics.

Wilson’s Warbler migrates from Mexico to Canada. Ken Miracle

Chuck Blair is a Wildlife Ecologist.

References

Wildlife Habitat Relationships. 1997. Colleen A. DeLong, wildlife extension associate, and Margaret C. Brittingham, professor of wildlife resources. Penn State University https://extension.psu.edu/wildlife-habitat-relationships

National Research Council. 1995. Science and the Endangered Species Act. Commission on Life Sciences; Board on Environmental Studies and Toxicology; Committee on Scientific Issues in the Endangered Species Act